Culinary Careers: The Food Scientist

Growing a vegetable garden is one thing, but extracting a leukemia-battling ingredient from the humble avocado — that’s a whole other order of accomplishment.

Food science, a relatively new discipline compared to ancient ones such as farming, involves the application of biochemistry, microbiology and a slew of other scientific expertise to the food system. Some food scientists blend their knowledge with other disciplines to do potentially wondrous new things with food. Others focus on food quality, safety and related concerns, from irradiation to genetic modification — key issues as we continue shifting from traditional, home-cooked meals to convenience and ready-to-eat foods. And for some, food science is a springboard into seemingly unrelated careers.

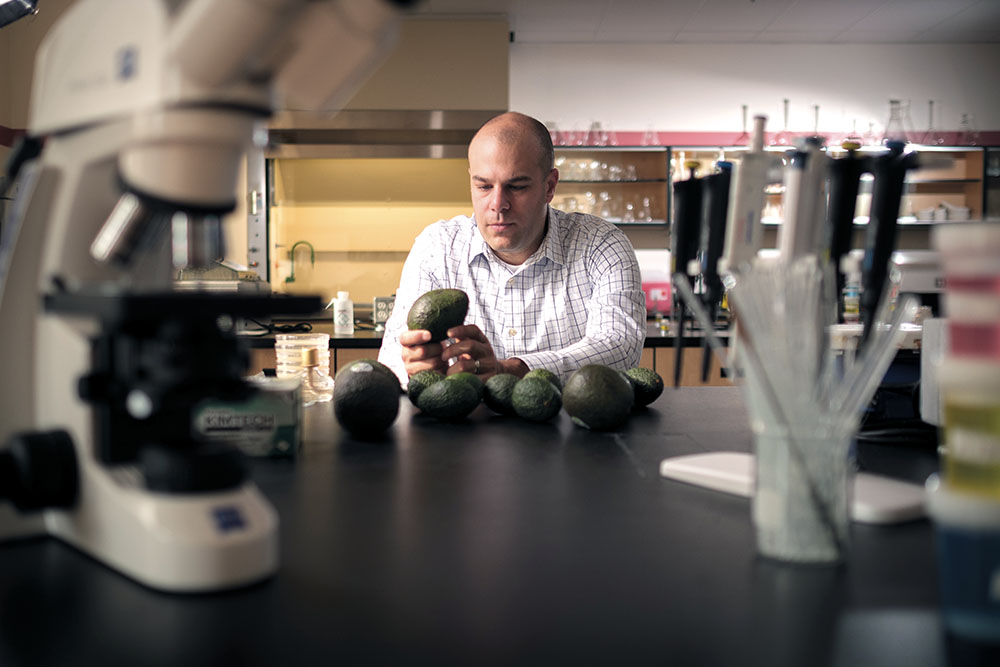

Paul A. Spagnuolo, University of Guelph

Avocados cure cancer! It sounds like the kind of Internet come-on for which only the truly desperate would fall. Thing is, there’s a very real possibility buried in that overstatement.

For the past several years, Paul A. Spagnuolo, an associate professor in the University of Guelph’s department of food science, has been investigating the leukemia-fighting properties of avocatin B, a lipid (or molecule) from avocados. He’s now well into a four-year, $200,000 study funded by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, a study Spagnuolo hopes will result in a drug that can actually be administered to a patient.

“We are extremely excited about the potential because it’s passed every step of scientific validation to date,” he says. “We’re moving to more sophisticated models of testing the avocado compound [and] how this molecule might be useful as a therapeutic.”

The work Spagnuolo is doing with avocatin B falls under the nutraceuticals umbrella, which is his specialty. Nutraceuticals are basically dietary supplements derived from food and sold in pill, powder or other forms to provide medicinal or nutritional benefits. They can include everything from vitamins and herbal remedies to fortified cereals.

Three-quarters of Canadians consume nutraceuticals and Spagnuolo’s work focuses on evaluating their actual therapeutic potential. In the case of avocatin B’s ability to fight acute myeloid leukemia, a rapidly progressing cancer of the bone marrow and the blood, Spagnuolo says, “Leukemia cells are very dependent on fat to survive, so avocatin B messes around with the ability of the leukemia cell to use fat and by doing so, causes the cell to die.” The messing around involves the inhibition of fatty acid oxidation. Without that oxidization, the cells can’t digest the fat they need to live and grow.

The Spagnuolo lab tested the ability of more than 800 natural compounds to kill leukemia stem cells and discovered that avocatin B was the most potent. It also targeted only the cancer cells.

Along with avocatin B, the lab is looking at nutraceutical effects on other chronic diseases.

“The ability to apply this knowledge and help someone is (my) driving force,” Spagnuolo says. “I had a cousin who passed away at 37 from stomach cancer. That lit the fire to say, ‘I want to contribute something that will mean there will be less of those stories in the world.’”

Despite holding undergraduate and graduate degrees in food science, Spagnuolo says he’s not a traditional food scientist. That’s because his PhD is in applied health sciences and he completed his post-doctoral fellowship at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto. Before joining the University of Guelph, he taught in the University of Waterloo’s School of Pharmacy.

“My background is very interdisciplinary,” he says. “What I do is based in food science, but I have other tools in the tool box.” That plays well into his goal: to marry food and pharmacology.

His involvement with food as a source of personal delight and scientific inquiry is long-standing.

“I come from a very traditional Italian family, where Labour Day weekend was spent making tomato sauce for the year. January and February, we made sausages and salami and prosciutto. My general interest in food stems from my Italian heritage.”

His interest in nutraceuticals grew from his love of sports and determination to be in peak physical condition. Intrigued by the fact that food has a drastic effect on the human body, he realized that today’s food isn’t the traditional foodstuffs our grandparents grew up with, that grains, for example, can be fortified with folic acid and milk with Vitamin C to promote health.

From there, it was just a few steps to realizing that while the Canada Food Guide aids in achieving a healthy lifestyle, it doesn’t help when someone battling cancer is looking for food to help in that war.

As well, he says, Health Canada defines a nutraceutical as a bioactive component from food that has a physiological benefit or can protect against disease. However, because of gaps in the research, “They don’t even look at these compounds as potential therapeutics. If there’s a demonstrated biological effect and it can prevent disease, why can’t it treat disease?

“So there’s this huge gap for us to systematically evaluate these food compounds and literally find the next cure for cancer. There’s a huge need to understand how these molecules work or don’t work so we can educate patients, so we can tell them, with great confidence, ‘Take this or avoid this.’”

There’s a mammoth demand for all kinds of nutraceuticals. A recent report by Market Research Future says that the expanding global nutraceuticals market — which ranges from dietary supplements and health drinks to the kind of nutrient additives for food that Spagnuolo flags — is expected to surpass US$319.6 billion by 2023.

Still, Spagnuolo says the mainstream scientific community doesn’t focus on nutraceuticals, and that he’s struggled to get research funding because there’s stigma associated with the kind of work he does. As a result, he’s been careful to concentrate mainly on the hardcore medical drug development stage of the compounds that fascinate him, which has resulted in funding.

“You’re fighting the Dr. Oz effect,” he says. “‘Sprinkle some turmeric on your eggs and you’re going to cure your cancer.’ It’s that kind of stuff I traditionally have to fight against."

The battle can be emotionally tough.

He says he’s lost sleep over the way his work can be misunderstood. He routinely gets emails asking if he has a product available for their ailing mother, spouse or child. That reminds him why he’s doing what he does, but also that patience is a critical component of the scientific process. “If we are sloppy, if we don’t do our due diligence, then we are selling false hope and that is the exact thing we don’t want to do.

“We have to make sure that, at the end of the day, when we do say, ‘Take this supplement. It might work for this,’ we want to make sure that we can say that with the most certainty we can, understanding that there is no such thing as a guarantee.”

Spagnuolo, driven though he is, also works hard to keep the big picture in mind.

“That’s the thing about research and patience. You might not be the guy who has the Eureka! moment, but that researcher behind you might read your paper and that helps define their Eureka! moment. That moment might be the moment that results in a paradigm shift that improves humanity. I don’t know — maybe I’m naive, maybe I just like to think that. But at the end of the day, that’s what turns the engine.”