Growing with the Fishes

To the untrained eye, the 400-square-foot greenhouse at Sir Guy Carleton Secondary School in Nepean looks like a typical greenhouse: trays of herbs and lettuces, a few pots of flowers, grow lights and the sun filtering in through glass panels and steamy air.

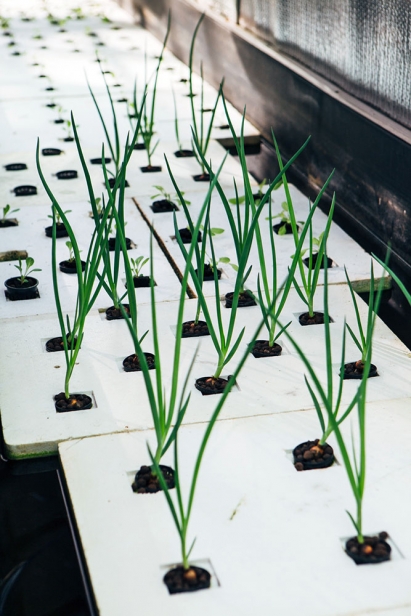

But look closely and you’ll see that the food plants are anchored on rafts floating in two parallel 45-footlong water beds. A network of pipes, pumps and other equipment connects the beds to two fish tanks, containing about 80 tilapia, to form a shared, recirculating ecosystem that nourishes the fish and the plants.

It’s an aquaponics system, one of very few in Ottawa, but a growing number around the world. In these systems, natural bacterial cycles turn fish waste into plant nutrients while the plants filter the water for the fish. Plants raised this way grow faster and require only about a tenth of the water that their soil-based counterparts do. It’s also a completely organic method of growing food because using pesticides, herbicides, hormones or medicine would hurt the fish, the plants or both.

The system at Sir Guy Carleton can produce about 100 pounds of food year-round — mostly lettuces and basil, along with tomatoes, kale, Swiss chard and strawberries. Urban Element occasionally orders the lettuce and basil, but most of the food goes to the school’s thriving culinary skills program.

“Kids need to learn that food doesn't happen magically in plastic bags, that it requires care, respect, appreciation, and time,” says Nicola Jarvis, who runs the culinary program. “We need students to learn to appreciate growing and producing food, because we’ll always need to eat and we need a future generation of farmers to sustain the world. And how good is it to be able to say ‘Pop down to the greenhouse, we need some basil.’”

No other school in Eastern Ontario has an aquaponics facility, notes Alan Abbey, a teacher in Sir Guy Carleton’s green industries program, one of a roster of vocational training programs the school specializes in. “Aquaponics is not only a sustainable urban farming technique, it offers students a unique learning experience as they seed, plant, maintain and harvest the food it produces.”

Although the term aquaponics was coined in the 1970s, the practice has its origins in the ancient world. The Aztecs raised crops on artificial islands in swamps and shallow lakes that provided nutrient-rich water and mud for the plants. The integrated rice paddy systems across Southeast Asia are also based on aquaponics.

These days, the practice is catching on in many countries as an eco-friendly alternative to soil-based farming, especially in an era of population growth, climate change, drought and soil degradation. In the U.S., there are thriving aquaponics operations in Colorado, Milwaukee, Chicago and Detroit. Canada is also home to a few, including the Mississauga food bank's Aquagrow Farms and an 1,800-square foot system, part of Fresh City Farms, a large urban commercial farm in Toronto.

The project at Sir Guy Carleton started about four years ago, sparked by a YouTube video that Abbey watched with Derek Brez, who heads up Sir Guy Carleton’s science and music department. “The video said that aquaponics is simple enough for a 14-year-old to do,” Abbey says. “Well, we have access to lots of 14-year-olds.” Inspired, he, Brez and colleague Nick Reyes attended an aquaponics workshop at the University of Guelph given by Noa Fisheries, an Ontario company that supplies sustainably raised tilapia. Armed with the new knowledge and assisted by students, Abbey began converting the school’s 30-year-old greenhouse into an aquaponics facility that could still accommodate some soil-based flowering plants for school fundraisers.

Setting up the new system was a steep learning curve, he says. “What’s out there is either really big or it’s homescale, but we wanted something in between.” An electrical outage, along with plumbing and filtering problems were just some of the glitches the team encountered. In addition, the work had to be done as cost-effectively as possible, using recycled and refurbished equipment, as well as plant seeds collected from Abbey’s organic home garden. And, new funding had to be secured for aerators, LED lighting and upgraded plumbing and electrical systems.

But it all came together. Today the facility is central to the urban farming skills program launched in February 2018 and has expanded to include a commercial rotary hydroponics system — another soil-less growing technique — they call the Omega Garden, along with a flourishing vertical garden fuelled by vermi-compost (compost from worm castings, shown to suppress plant disease and pests).

While aquaponics take hold at the Nepean high school, a home-based aquaponics operation called Miner Aqua Green Foods aspires to bring more organic produce to consumers. Based in Curran, southeast of Ottawa, it’s a labour of love for Frederick Miner and his daughter Kassandra, who launched the project early in 2017. Frederick had run a successful insulation business in Hawkesbury until an attack of Lyme disease left him with chronic health problems and forced to find a new line of work. He wanted to pursue something that would draw on his love of food and childhood experiences on his father’s hobby farm and settled finally on aquaponics as an environmentally responsible way to produce clean food.

He threw himself into the research, taking online training from Australian aquaponics guru Murray Hallam. Once Miner and his family moved to Curran, he transformed the garage on the property into a 20x30-foot aquaponics greenhouse. “It was lots of work, but lots of fun. I had to be innovative and find inexpensive materials that would be safe, functional and allow the system to expand,” he says. For example, he would have paid about $65,000 for a commercial grade set-up. “Instead, for less than $7,500, we developed our own system using mostly recycled materials and dollar-store accessories.”

Depending on the plant, Miner used one of six soilless growing systems, including vertical pipes with divots to house the plants, floating water tables and a coconut fibre-vermiculite mix with half-inch crushed stones for the plant roots. “Earth is too compact, it inhibits growth,” he says. “With aquaponics, it only takes 21 to 24 days to bring a plant from seed to harvest.” In the first year of operation, Miner’s soilless systems produced salad greens, Red Russian and curly kale, spinach, herbs, strawberries, three types of tomatoes, squash and cucumber.

Kassandra, who handles marketing and customer relations, sells produce mostly at the farm gate, with some of it going to the Fox & Feather Pub and Grill on Elgin Street. But in the long-term, she and her father want to supply one or two restaurants consistently and to have a presence at the ByWard and Landsdowne markets. In addition, they have begun to replace the koi and goldfish in their system with fish, such as tilapia, which could one day be sold along with the vegetables and fruits.

In December 2017, the Miners suffered a setback — an electrical fire damaged the greenhouse and contaminated the plants. But they quickly bounced back, making the necessary repairs and installing a new floating-raft growth system. At the same time, they’re trying to raise money for a larger, four-season greenhouse through channels, such as partnerships with community development groups.

Through it all, they continue to follow their own formula for success in the blossoming world of aquaponics: time, patience, dedication, and a love of clean food.

Sir Guy Carleton Secondary School

55 Centrepointe Dr., Nepean, Ont.

sirguycarletonss.ocdsb.ca, 613.723.5136

Miner Aqua Green Foods

3404 Boudreau Rd.,Curran, Ont.

mineraquagreenfoods.squarespace.com, 613.716.5373