Helping the Honey Bees

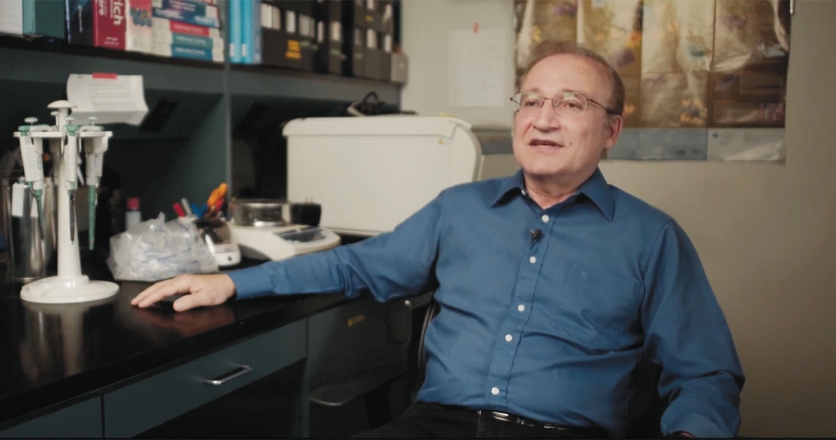

Oil of oregano is experiencing a surge in sales as more people reach for it amid the COVID-19 pandemic with hopes it will boost immunity through the cold and flu season ahead. Ernesto Guzman has also been known to reach for the essential oil, loaded with antioxidants. But it hasn’t been to protect his own well-being. Guzman, who heads the Honey Bee Research Centre at the University of Guelph, has spent years testing how effective oil of oregano is at helping honey bees build immunity against the biggest threat to their survival: the Varroa destructor mite.

The name says it all. The Varroa destructor, a parasite that feeds on bees’ fat tissue and hemolymph — think of it as bee blood — can cut a bee’s life expectancy in half. And it’s not a stretch for it to obliterate up to 30 per cent of bee colonies worldwide every year.

Finding something to combat the Varroa destructor is critical, not just for the honey bee’s survival, but for all of humanity, which depends on the buzzing black and yellow insects to pollinate one third of the food crops we eat.

In addition to testing oil of oregano, Guzman and his team of researchers tried out thyme and clove oil and oxalic acid. While humans might be sold on oregano oil as part of their cold-and-flu season arsenal, it turns out it was the least effective of the essential oils against the Varroa destructor in bees.

Still, it’s better than any alternative made by humans, Guzman explains.

“The advantage of using these natural compounds [instead of antibiotics] is we don’t pollute the honey, we don’t promote resistance and it’s less expensive than synthetic miticides,” Guzman says.

Guzman has devoted his life’s work to studying honey bees. His career in honey bee research took flight after a guest speaker at his high school in Mexico lectured about the insects and their innate altruism, including working and living for the greater good of their hive.

Fascinated by what he heard, Guzman began reading everything he could about honey bees. He was captivated by their social structure and their willingness to sacrifice themselves for the colony. That lack of individualism appealed to an idealistic teenager, who eventually acquired hives of his own.

Guzman headed to veterinary school in Mexico City after he finished high school. Later, he devoted his graduate studies to all things bees, earning his masters and PhD in entomology from the University of California at Davis.

Through it all, he never lost his admiration for honey bees’ collectivism, even if he grew evermore disenchanted with his fellow humans' mentality of every person for themselves.

“The perspective I have is the same. [Bees] contribute to life in their community,” Guzman says. “But I’m not such a dreamer that human societies will change for our communities. We’re too selfish.”

He remains undeterred, however, in his research to find potential solutions that will not only save his selfless muses, but ultimately the self-centred species that depend on them.

His focus at the University of Guelph for the past 15 years has been to find — and alleviate — the biggest culprits for colony collapse disorder, which is the exceptionally high rate of bee deaths that have happened every winter since the late aughts.

With financial assistance from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Guzman’s job was to rank the reasons for bee deaths in order of their impact on bee survival.

Varroa destructor tops the list for winter deaths of honey bees throughout much of the world. But bees also have to contend with Nosema ceranae, a fungus that damages their digestive tracts, debilitating them and spreading through colonies in spring and summer.

Rounding out the list of threats to bee health and survival is pesticides, specifically neonicotinoids used to protect genetically engineered field crops, including corn, soy and canola. Nearly one-third of bee carcasses examined in studies about the impacts of pesticides show high levels of “neonics.” Those findings have inspired countless calls for outright bans on their use in everything from agriculture to flea treatments for pets.

Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) is in the process of phasing out the contentious pesticide in farming. It’s already banned its use on some crops, including orchard trees, and it no longer allows spraying of some vegetable and berry crops before or during bloom when bees are most likely to collect pollen.

It’s those changes that are the entire point of Guzman’s research.

“Research cannot give solutions to mortality from pesticides, but it can give information to regulate the use of pesticides,” he explains.

Still, he is on a quest to solve the Varroa destructor’s threat with essential plant oils and organic acids and deal with Nosema ceranae with other natural compounds. In the latter case, Guzman is testing chitosan, a supplement made from crustacean shells and pre- and probiotics to stimulate a bee’s gut and induce immunity similar to a vaccination.

Initial studies show such supplementation can cut the effects of Nosema ceranae in half. Guzman and his team also tested supplements in 100 colonies in the field. They found two gut -health boosters to be particularly promising. Not only did they reduce infection, they also increased the treated bees’ life expectancy over those that went without.

That’s led him to try to devise a formulation that beekeepers can use themselves to help their hives, especially those who ship their colonies elsewhere to help with crop pollination. When beekeepers in Ontario, for example, send their hives east to give life to New Brunswick’s blueberry crop, it stresses bees out, Guzman says. The pollen that they forage is also the equivalent of eating “McDonald’s hamburgers for a whole month. There’s going to be some nutrients missing there.”

So they need all the immunity-boosting nutrition they can get.

Guzman hopes someone will commercialize a formula to market to beekeepers. But it is a high hope given the size of the beekeeping industry compared to a supplement marketed for human health.

“Maybe if we were working on human disease, there is more money in it and [someone] will produce it,” Guzman says. “We come back to the issue… where humans are selfish and greedy.”

Meanwhile, he and his fellow researchers share their findings in scientific journals to inspire other scientists to build on their research. They also offer up the information to beekeeping associations and in University of Guelph-produced videos that have been viewed five million times in 170 countries.

As such, some see the merit in the work scientists and researchers are doing on bee health at Guelph, which also includes breeding Buckfast bees, a species highly resistant to tracheal mites, which are known for having harmful effects on bee colonies, too.

Guzman is the Pinchin Family Chair in Bee Health thanks to a $1-million gift in 2016 in the memory of Donald Pinchin, a scientist and philanthropist who grew up on a farm and orchard near Toronto.

The Riviere Charitable Foundation also contributed $6 million toward constructing a new $12-million honey bee research centre to replace the dated — and small, but mighty — building where Guzman and his team currently carry out their work, teach 700 students a year and keep 300 colonies.

Billed as a “hive of research and outreach,” the new centre will be the world’s largest teaching and research apiary when it opens in late summer 2022. “When we retire, we’re leaving that as an inheritance for the next generation of honey bee scientists that we’re also training,” Guzman says.

In the meantime, it’s where he, his fellow researchers and all those students will keep busy as bees with their work. And, in the process, they’ll defy the individualism that Guzman railed against when his interest was piqued by honey bees all those years ago in Mexico.

“We’re trying to have an impact. The knowledge from the research we’re trying to apply it to the practical aspects of beekeeping so others can benefit from it. And we don’t make a single cent from it,” Guzman says. “It’s the whole team that has that collective mentality here. I have students who would come to work at midnight here. Everybody would help everybody when needed.”

University of Guelph: Honey Bee Research Centre

308 Stone Rd., E., Guelph, Ont.

honeybee.uoguelph.ca | @honeybeesatuog