The Fortunate Seed

Every story passed on through generations shifts and takes on new shapes. Parts are exaggerated or selectively forgotten. Fact and fiction are fused in a seemingly inextricable knot. The following story is just that — a loosening of this knot to understand a piece of our food history. For history has proven that this apple was no ordinary apple.

There are some things we know for sure: Some 200 years ago, a man found an apple tree with some darned good apples. We also know that every McIntosh apple tree that stands today can attribute its existence to these humble and somewhat speculative beginnings.

It all began in Dundela, Ont. But how it first arrived is pure conjecture. Apples aren’t native to Canadian soil, so it’s supposed someone must have pitched a few cores on this particular plot of land. Mother Nature accepted the gesture and encouraged the sun and the rain to grant the seeds’ wish to root. It was a gift waiting to be discovered.

Meanwhile, further south on the continent, in what is known as the Mohawk Valley of New York State, the future beneficiary of this gift was sensing change in the air. John McIntosh (1777-1845), the son of two Scottish immigrants who had remained Loyalists throughout the American Revolution, was ready to spread his own wings. Rumour has it that in 1796, he bid farewell to his family and made his way across the border following a love never to be realized.

McIntosh planted his roots in Upper Canada and learned to farm on Canadian soil. It was here that he met Hannah Doran. They married in 1801 and farmed along the St. Lawrence until 1811 when, for some unknown reason, other than to succumb to the fate that would befall him, he swapped his land with his brother-in-law’s. John and Hannah took a large plot in what was known as the Matilda township of Dundas county.

Each day, McIntosh would work the land for planting. But on one particular day that year, something extraordinary happened. As he was battling the brush that Mother Nature had left, he discovered a few apple saplings.

He carefully dug around the base of each tree, brought them home and planted them for his family to nurture. Of these 20 or so saplings, some proved to like their new home, though all in different ways. For, not everyone knows, the old saying “the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree” is a curious expression — because every apple makes new trees unlike itself. Unlike most seeds, apple seeds have been granted creative liberties to form whatever new apple variety they desire.

Back in McIntosh’s garden, where his 11 children would grow into their own personalities, one of these trees in particular, was very happy. To prove it, it gave his family the most beautiful red and green apples they had ever tasted. Perfect for eating right off the tree and wonderful in the pies and anything else that Mrs. McIntosh decided to cook. She was so fond of that tree and its apples that the family and the neighbours came to call it “Granny’s apple tree” because of the way she nursed it.

“Granny’s apples” became popular among the locals. McIntosh’s family realized their popularity and with coaxing from neighbours and friends, decided they would need to change the name of these sweet red wonders. They settled on their family name, with this particular favourite dubbed the “McIntosh Red.”

The family enjoyed the McIntosh Reds borne of their tree, but could not figure out how to plant more trees to match this idyllic wonder. It wasn’t until sometime around 1835 that John McIntosh and two of his sons, Allen and Sandy, met an individual who was able to explain the art of grafting, opening the door to multiplying the McIntosh-bearing tree population.

Allen and Sandy became particularly adept at carefully cutting the new growth, fraught with healthy buds, inserting it into a T-shaped slit on another piece of rootstock and binding the two with rubber so that they may grow as one and proliferate.

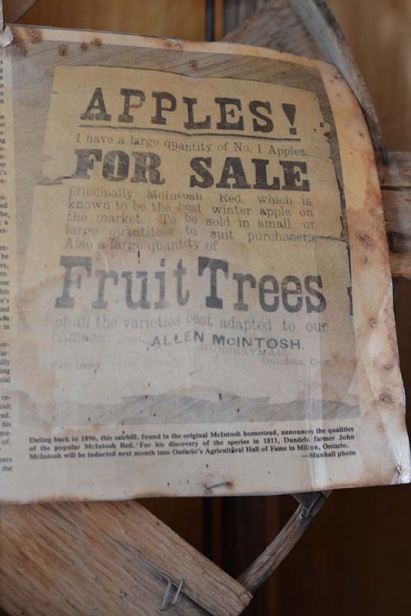

It is said that Allen McIntosh was the who oversaw the establishment of a small orchard and nursery on the family homestead. He also initiated the widespread promotion of the apple tree and its apples, selling and even giving away McIntosh seedlings to people all over eastern Ontario.

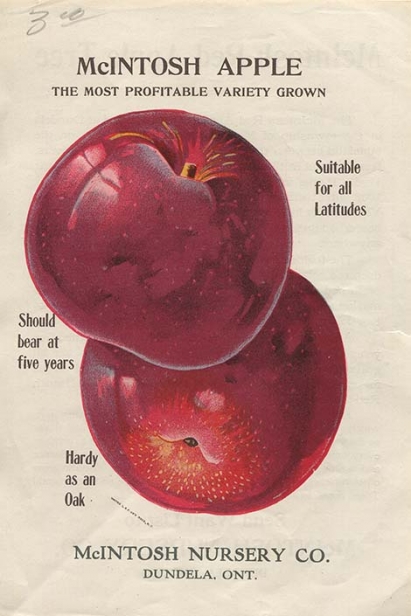

Despite the popularity of the Mcintosh within the district, it wasn’t until 1876, when E.D. Smith, of Winona, Ont., president of the blossoming E.D. SMITH food empire, tasted the McIntosh that the apple really took a hold on the market. With his endorsement, this apple took root across Canada and the United States.

Many orchards, including Smyth’s Apple Orchard, located less than a kilometre east of the original McIntosh homestead, prospered as a result of this. Its founder, Samuel Smyth, propagated new saplings from the original McIntosh tree after working as a farm hand for the McIntosh family. The Smyth orchard still thrives as a family business, with more than 100 acres of fruit trees and a large variety of apples, including the McIntosh and McIntosh-hybrid varieties.

Today, the McIntosh apple remains a key player in the apple market. According to the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, this apple remains the highest grossing apple variety in the province. A total of 249 of the major fruit crops in Eastern Ontario are apple. While this includes the famous McIntosh Reds, the McIntosh has also shared its genes with a number of other popular apple varieties such as the Cortland, Empire, Jersey Mac, Lobo, Melba, Paula Red and Spartan.

The original McIntosh tree continued to bear fruit for nearly 100 years — long after John McIntosh’s death. Even after being partially hit by a fire in 1894, the steadfast tree continued to produce apples on one side for another 10 years or so. The town, which for a time was called McIntosh Corners, has since been renamed Dundela and that once-famous tree is now gone.

A drive through this town will lead you to a few old plaques and a withered property. The McIntosh family, though they number in the thousands now, does not live on the old homestead. Across the street, at the corner of McIntosh Rd., there is a quiet, almost lonely looking playground. A large colourful mural depicting the apple’s history stands in solemn solitude. But those apples — those juicy, crisp, ready-to-eat and easy-to-bake apples — retain a nostalgic hold on all of our memories.