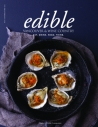

'Rural Cooking and Good Cheer'

There’s nothing rustic-looking about the plate chef Elliot Reynolds has just put down on the bar of Bloomfield Public House. Across the middle, it features a marrowbone, which is cut open and nests some Lake Ontario house-smoked white fish, flaked and carefully placed in the deepest recess of the bone, on top of the fish, there’s piped Duchess potatoes. With the potatoes nicely presented, he drizzled them with melted butter and it all went in the salamander to crisp the top of the potatoes. Once warm, Reynolds removed it and covered the whole thing, and the plate, with an herbed caper and olive oil dressing, featuring celery, fennel, chives and parsley.

Asked to create a dish that represented himself on a plate, Reynolds offered this small, decadent creation. And although it’s refined and sophisticated in presentation, it’s ultimately a rustic dish that speaks to what he does at Bloomfield Public House — he describes it as “rural cooking.” Asked if it’s elevated rural cooking, he bristles. There’s no question it is, but labels aren’t his thing, and he presents all of his dishes with a hearty serving of modesty.

Reynolds and his wife, Laura Borutski, ended up owning the restaurant in the heart of Bloomfield by happenstance. They had owned and run The Hubb, a restaurant located within Angéline’s Inn just up the street, for five years and decided they were, as Reynolds put it, “tired.” The plan was to close The Hubb and go travelling for a year, something the childless culinary couple — he, a chef; she a sommelier and the front-of-house manager — had done before.

But that plan was scuttled after they closed The Hubb and the building that now houses the Public House came up for sale. They couldn’t resist buying it and embarking on another adventure in the town they love. The renovations started immediately. Originally a grocery store, the building had been home for 60 years to the local bank, which, by the time it went up for sale, contained no services other than those of an ATM. The inside was a mess. Also set up within the building was the County Magazine shop, which moved down the road to the tourist bureau when the couple bought the building. Since it had always been a public building, that informed their decision to call the restaurant “Public House.”

Renovations were extensive and exhausting as they did much of the work themselves. They did their best to preserve the unique white and black building’s character, leaving the large vault in the back of the main seating area, for example, and another one in the basement. The latter now serves as a walk- in fridge. They stripped the building of its insides because it needed so much work and when they got back to cement walls, they decided they liked them just as they were and left them bare. Their bareness is now punctuated by large bright yellow lamps that jut out from the walls. The husband and wife painted the cement floors they uncovered, but then decided the floors looked better scuffed so they sandblasted much of the paint off again.

The heart of the restaurant may well be just outside the side door — a hand-built stone smokehouse that sits adjacent to the side deck. Reynolds and a couple of friends spent a gruelling 10 weeks building it. They dug a two-foot hole, laid foundation, then blocks, cement, gravel and the top foundation pad before they could do the stone work on the actual smokehouse part.

“I said ‘Let’s do it right,’” Reynolds remembers.

Upstairs, they’re turning what used to be a two-bedroom apartment into a private dining space that will seat about 30. The restaurant opened in the fall of 2018 and they were planning to have the upstairs done in time for this summer’s tourist season.

Inside the kitchen, they also honour the building’s heritage, using as many County ingredients as they can. Borutski stocks the bar with local wine, beer and spirits, while Reynolds buys as many ingredients as he can from local farmers, fishermen and meat producers. The lamb comes from Dana Vader’s County farm; the pork also comes from a local farmer; the fish from Lake Ontario and, when it’s open, Reynolds buys vegetables from Hagerman’s farm stand just up the street from the restaurant. While Reynolds is sitting on the front deck on a sunny May day, talking about his culinary philosophy, Aaron Armstrong from Blue Wheelbarrow farm drops by with two pounds of freshly picked sorrel that went into that evening’s pasta.

Back to his roots

Reynolds is a Southern Ontario boy. He grew up in tiny Stirling, north of Belleville. The County was always a place he visited on vacation.

“It was always about the beach, a place to go camping,” he says. “It was a humble destination for a lot of people.”

He thinks it’s changed since his childhood — he’s 37 now — but the changes are for the better.

“I think there’s a lot of successes in the past 10 years that have happened and needed to happen,” he says. “If there’s a need for housing or more rentals, the market will increase. If there’s a need for people to eat, then people will open more restaurants. In Bloomfield, there are four now. The County’s always been a special place. I don’t want it to lose its charm. People are still fighting for that.”

After growing up in Stirling, he worked at a now-closed roast beef house called Two Loons before heading to Ottawa to work in kitchens here. He began his Ottawa time by getting some experience in a hotel kitchen at the Château Laurier. He then worked at Social, under well-known Ottawa chefs René Rodriguez and Steve Mitton. During his time in Ottawahe succeeded in getting his chef’s papers through the apprenticeship board, but after his time at Social, he decided he wanted to travel and then study, which he did at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, N.Y. Following that, he moved to the West Coast, chasing his affinity for seafood.

“I learned quite a bit about seafood on the West Coast and then I did some travelling down south [Costa Rica and St. Martin] where I ran a couple of kitchens,” he says, always careful not to toot his own horn. He later opened a Mediterranean restaurant during a one-year stint in Russia before moving back to Canada — the Banff Springs Hotel, to be specific. He met Borutski in the kitchen there. At the time, she was cooking, but she soon changed her focus to front-of-house and pursued oenologystudies in Vancouver and Ottawa.

The two spent two and a half years in Vancouver, and then Reynolds took a job as the chef for the 2010 Winter Olympics at Whistler. They then travelledAsia for three months before moving back to Ottawa. Borutski worked at the Wellington Gastropub as front-of-house manager for three years, and Reynolds was the head chef at Dish Catering for two seasons before the executive chef position at the ClaramontInn in Prince Edward County came up. Reynolds had taken his wife, who was born and raised in Calabogie, to PEC previously and she’d made it clear she wanted to live there. Problem solved.

He did two summers at the Claramountbefore the couple took over the restaurant at Angeline’s Inn.

Culinary influences

Rural cooking and appreciating good ingredients are what defines what he’s doing now, but Reynolds’ influences are varied.

“I feel a lot of influence from the West Coast when we were using a lot of seafood and stuff that’s just so natural,” he says. “You could be pulling it out of the water and putting it on the plate. The little fishing villages in coastal areas are pretty special.”

And while he’s capable of complicated dishes, and has cooked them over the years, he notices the more time he’s in the kitchen, the simpler his cooking is becoming.

“I tell my chefs, ‘let’s just talk about big flavours and only four or five ingredients,’” he says. “The smoked white fish dish, for example, takes a great piece of fish and smokes it simply. It’s really about simplicity, but we’re still going to have fun with it.” The whimsy, in that case, comes from plating it on the marrowbone.

“I guess it’s simplicity with a twist, but I’m not trying to label things,” he says, adding that he doesn’t use the expression “farm-to-table” anymore because he feels it’s being misused and misrepresented. “We think of what we’re doing as ‘rural cooking and good cheer’ — we’re approachable.”

“We do more nose-to-tail than anything,” he says. “My sous- chef has been running the charcuterie program for a while. We do our own cured meats, mortadella, dry-cured sausages, we smoke our own hams from the neck area of the pig. We’re slowly working toward small-batch charcuterie that we can retail from the restaurant. Charcuterie is really at the heart of our food program.”

He also identifies strongly with southern cooking, though he’s never worked or studied in the American South.

“A lot of my cooking is rooted in the south,” he says. “I am drawn to that cuisine. I guess I’ve always had an affinity for smoked things.”

To that end, the smoker influences what he’s doing now and the inspiration for it was from many of the homesteads in the county — a smoker was often a fixture on the early properties. “[When I think about influences,] it keeps coming back to the smoker. I never wanted this to be a barbecue joint. It was more about the smoker being a fixture here and using it.”

Case in point: At Easter, they roasted a whole lamb asado-style over an open fire in the smokehouse.

An all-day gathering place

The branding for the new restaurant was a struggle. They wanted to get across that it was an approachable place — a place to grab a coffee mid-morning; a pint mid-afternoon and a bite any time of day, including brunch on Sundays. The logo features a chubby chickadee — an Ontario bird — wearing a top hat. “He has a top hat and forks for feet,” Reynolds says, the implication being, it would seem, that you’ll get something unexpected inside these doors.

They decided to keep the colours — black and white — and add small colourful flourishes such as the bold yellow lights in the dining room. The same black and white even appears on the stair risers heading up to the private dining space.

“As we go along, we’re just going to continue to discover what the County is,” Reynolds says. “We’ll continue to forage, use the smokehouse, understand and use local grains and in-season products — celebrate rural cooking. In a nutshell, that’s what we’re about.”

Bloomfield Public House

257 Bloomfield Main St., Bloomfield,

613.393.9292 | bloomfieldpublichouse.ca | @bloomfieldpublichouse