A Time Capsule in a Jar

When Andrea Glenn, a former literary agent, met Russell Gibbs, a graphic designer, she knew nothing about bees. Now, eight years later, she’s a walking talking bee encyclopedia. She’s also two thirds of the way down the road to becoming an internationally accredited honey sommelier. Meanwhile, Gibbs, now her husband, comes from three generations of beekeepers. To say he has the bug would be an understatement — he has literally millions of bees under his care, spread across 30 bee yards in the Vankleek Hill area to the east of Ottawa.

On the day of edible Ottawa's visit, Gibbs was called away, with the couple’s five-year-old son Boyd, because the couple had just had its first bear attack on their home bee yard. Five hives have been destroyed and several others tipped over, but the queens were still to be found on some frames, and those ones were salvageable. The attack is part of the changing nature of beekeeping these days — to expect the unexpected, Glenn explains. Be that colony collapse or hives just disappearing on a puff of wind, or in this case, bears who have developed a taste for sweet, sweet honey. “Apparently, during COVID, the bears discovered the empty highways,” she says, “and this allowed them to go farther, faster and to discover wider sources of food. So now they know where to go.”

Gibbs and Glenn moved to the Vankleek Hill area seven years ago when their city lives — she in Toronto, he in Hamilton — were no longer fulfilling. “We hungered for an opportunity to do something we were truly passionate about,” she says. “Russell was feeling like his sideline beekeeping operation was more than just a hobby.” At the time, he was keeping approximately 30 hives. Now the operation numbers over 300 hives spread within a 30-mile radius. The couple hopes to build it to between 450 and 500.

In 2017, Glenn and Gibbs went property hunting in the region. They were pleasantly surprised by what they found, comparing prices to farmland in southern Ontario. They bought an 111-acre farm, complete with airstrip, a small red-brick 1870s house and a lovely old barn in great condition, just a few miles from Gibbs’s family farm, where the beekeeping all began. Then they approached Gibbs’s uncles Tim and Peter, to see if eventually they might sell them the Gibbs honey business, founded by Russell’s grandfather. None of them could quite believe their luck. The uncles had been hankering to retire for years, and Glenn and Gibbs were able to keep a family business alive and buy the existing hives. Everyone was happy.

In the intervening years, Glenn and Gibbs have thought hard about what they want to do with their property and the honey. “It’s very important to us to bring life to this property,” Glenn says. By this she means both in the form of improving the habitat and bringing people to the farm to animate it and keep it vibrant. They have planted the former airstrip, about three acres, with wild pollinator flowers such as oxeye daisies, bee balm, echinacea, fireweed, and they have broadcast seeded a further 10 acres elsewhere on the property with wildflowers. They have also worked with Alus Canada, an organization that helps farmers build nature-based solutions on their land to sustain agriculture and biodiversity for the benefit of communities and the future. Plans for the future include picnics in the wildflowers, winter snowshoeing through the woodland trails and events in the barn, as well as workshops and potentially an Airbnb. Currently, they offer hands-on beekeeping, apiary tours, sommelier-guided honey tastings and, in a first for 2024, a drystone walling workshop.

A new, purpose-built honey house stands proudly to the side of the majestic barn, clad in rapidly greying siding, milled from trees selectively felled on the property. It is here that raw honey becomes liquid gold. Huge stainless-steel tanks wait to welcome the first harvest, sometime in early July. They will fill the 7,500-pound tank many times during the season, producing between 30,000 to 50,000 pounds of honey. There’s a giant freezer, useful for storing comb, which keeps it from crystallizing and away from the wretched wax moths.

“The provenance of our honey is extremely important to us,” Glenn says. “We only ever use honey made by our bees, produced from our hives.” The same goes for wax. The comb is rotated and melted down every two to three years, to ensure it remains clean because you just don’t know where a bee might have been foraging. And Gibbs’s candles are made only from the wax cappings — the tiny bits of wax that bees make to seal off a honey-filled hexagonal cell. The cappings are then highly refined so that they are clean, producing rich, smooth, dark yellow candles, both dipped and molded, that smell strongly of honey.

This summer, Gibbs’s line of jarred honey and cut comb launched at Whole Foods Markets across Ontario. They have a partnership with Farinella in Ottawa to produce hot honey for drizzling on pizza, and their honey is sold at Jacobson’s on Beechwood Avenue and Pot and Pantry on Elgin. Restaurants in Toronto, such as those under the Terroni umbrella and the Michelin-recommended Pompette, use Gibbs honey in their kitchens. “Part of the passion is getting to know the chefs,” Glenn says, “and I love to see what they do with the honey.”

Plans for the future include working with chefs to offer honey flights, and honey and cheese pairings. They also plan to make their own mead. Styles will include a cider-like effervescent one with five to six per cent alcohol and another with herbal infusions. “We are just waiting for the licensing process to move along,” Glenn explains.

The sweet sommelier experience

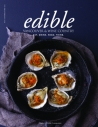

The honey tastings take place in the soaring barn, furnished with a few mis-matched vintage tables and chairs and white tablecloths billowing in the breeze. Glenn will be a fully certified honey sommelier, accredited in Italy by the National Register for Experts in the Sensory Analysis of Honey when she passes the level II advanced course exam in December. She will be the first Canadian to reach this level and to be registered with the authority. Accreditation is a process much like that of becoming a wine sommelier.

On this Sunday afternoon, the tasting features six different honey types. Gibbs’s own, one from Hudson just an hour east down Highway 417, one from France and the remainder from Italy. The contrast is striking and extreme. Some are delicately floral, others are robust and bitter, and there’s plenty in between. Glenn is a talented guide, showing how to first smell the honey, then taste and filter out the various floral, fruity, aromatic and vegetal notes. At the start of the experience, she makes participants do a simple but surprising exercise — one that we won’t spoil for you here — to illustrate the difference between flavour and taste. “I believe honey is one of the best expressions of terroir,” she says.

You’ll likely be convinced after the tasting, too. These honeys have nothing to do with the Billy Bee product found in the supermarket, not least because they are single varietals (like wine made from just one grape). They come from one producer. And that, at a time when the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has found that about 20 per cent of honey in Canada contains ingredients other than honey, is a big deal.

The tasting ends with a slice of honey cake, made by Glenn. She admits to having always been interested in food, but credits the pandemic with deepening that interest. While she’s not a person who remembers life events by taste — like Proust’s legendary madeleine — she has more of a smell memory. “It’s a sensory journey,” she explains. “What you are tasting and smelling is an environment time capsule in a jar.”

Gibbs Honey

501 MacCallum’s Lane, Vankleek Hill, Ont.

gibbshoney.com | 613.699.1131 | @gibbshoney