The Big Picture — Jane Rabinowicz

Jane Rabinowicz seems a bit like a kid in a candy store when she gets her hands on Strawberry Popcorn. “This one is my favourite,” she says with a grin. But her sweet tooth isn’t for sugar, even though many of the corn varieties being developed on Canada’s Experimental Farm are packed full of it — just not the kind you would want to eat.

“The plant breeding happening here is entirely focused on conventional agriculture,” Rabinowicz says. She holds up a dark mahogany cob shaped like a small pine cone. Its seeds are among hundreds of different varieties stored in the seed bank of this plant-breeding station. Strawberry Popcorn is an ornamental variety and there is another one just like it is pinned to a display on the facing wall, along with about a hundred others. The ornamentals boast a collage of brown, red and deep purple kernels. Most of the cobs, though, look rather like the corn we all know, except each is its own unique species — new specialized breeds and hybrids are developed through several trials of cross-pollination attempting to uncover desired characteristics, such as sugar content, in a single cob.

It’s the plant-breeding possibilities that excite Rabinowicz, who calls herself a “super seed nerd.” But the diversity on display is a bit of a mirage. Only select varieties will make it past the tests in these urban fields, where they will be grown to seed and sold to farmers across Canada. Those swaths of corn dominating our arable land are destined for big industry — feedstock and biofuels — a fact that quickly quells Rabinowicz’ enthusiasm.

“We’re in a diversity crisis,” she says. As executive director of USC (formerly the Unitarian Services Committee) Canada, Rabinowicz is leading the Ottawa-based international development organization which has been at forefront of biodiversity conservation for nearly three decades.

The picture is rather bleak. The global loss of agricultural biodiversity stands at 75 per cent in the past 100 years and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations estimates we’re on track to lose a third of what remains by 2050. While a loss of variety in the field might make for a dull cornucopia, it's the loss of resiliency that is truly alarming.

Climate change is shifting the playing field, changing weather, soil and disease patterns and leaving crops that cannot adapt fast enough and therefore susceptible to failure.

The solution, Rabinowicz says, is seeds. But not just any seeds, we need diverse, locally adapted seeds that are bred for ecological agriculture practices, because good seeds are where good food begins.

"If we are thinking about the food of the future,” she says, “everyone wants to grow more sustainably — be it a conventional grower, a certified organic grower or a grower who is practising organic methods. So what is that? It's enough food, it's healthy food, but it is also food that is produced sustainably."

Rabinowicz, 37, was first recruited by USC Canada in 2011, but her resume was already impressively stacked with two decades of food-justice work. During high school in Toronto, she volunteered in community gardens and soup kitchens; in Montreal, while enrolled in environmental studies at McGill, she volunteered for a youth-led non-profit called Santropol Roulant, where she helped grow, cook and deliver food by bike to seniors across the city. It was an experience that, she says, was life changing. “It was there I realized food is a vehicle for change and not an endpoint.”

It was also a vehicle for her career. After graduating from McGill, she applied as an intern at Santropol Roulant and wound up working there for 10 years, serving as its executive director for her last five years. She then accepted a position as director of development at the Québec ecological organization, Équiterre, where she worked for 16 months. But Rabinowicz had her heart set on being a leader at the national level — that’s when USC Canada came calling.

“Everyone knows how fundamental food is, the importance of local, sustainable, healthy food, and there are a plethora of organizations working on that,” Rabinowicz says. “USC Canada’s niche within that system is biodiversity, seeds, ecological agriculture and farmers' rights. Seeds are the starting point.”

USC Canada has been working on seed saving and breeding initiatives globally since 1989, when it launched its flagship program, Seeds of Survival, during a mission in Ethiopia. Civil war and drought had put local farmers in a dire situation. Facing starvation, they couldn’t wait to get their seeds in the ground and started eating their stores. USC Canada, which had been engaged in global relief efforts since its inception in 1945, worked directly with farmers and local organizations to save the seeds it had left, multiply them quickly and build stores through community seed banks. The methods focused on participatory plant breeding, on-farm conservation and ensured that women and youth were given autonomy over their farming practices.

Seeds of Survival would become the crux of USC Canada’s missions abroad, eventually spreading to 11 countries across Latin America, Africa and Asia, launching an ongoing legacy within the global food-sovereignty movement. “I like to think of us as a technical organization with social-justice values,” Rabinowicz says.

It wasn’t until 2011 that they brought it home, when Rabinowicz came on board to design USC Canada’s first-ever national program, where the loss of diversity is exasperated by multi-national seed companies that control more than 75 percent of the world's seed market. First, she needed to find out who was out there, working as the hidden heroes of the food system.

“I spent my first year on the road,” she fondly remembers, “I went coast to coast, travelling across Canada talking to anyone and everyone who was working with seed.”

All told, she met with more than 1,000 farmers, activists, researchers from academia and government, people who were testing and breeding seeds, trying to glean what was happening in the seed movement and how they could work together. “Our philosophy is about working in partnership and in respect — in talking to organizations that are already active and finding out if we can work together,” Rabinowicz says. “That was really at the heart of building the Canadian program.”

When she returned to Ottawa she set about pulling the pieces together. Farmers provided the backbone of the program, people such as Shelley Spruit of Against the Grain and George Wright of Castor River Farms, to offer workshops and training on seed saving and breeding in their local region.

“Our work in Canada is built on what farmers like Shelley and George have been working on for decades,” Rabinowicz says, “They are biodiversity champions. These are the folks who have realized the importance of biodiversity on their farms and through their businesses."

She partnered with researchers at universities, even tapped the trove of plant breeders at Canada’s Experimental Farm, for their expertise and help on an organic corn-breeding program.

Seeds of Diversity, an organization of seed savers — mostly gardeners — that exchanges upwards of 7,500 rare varieties through its 1,000-member network, became the main partner behind The Bauta Family Initiative on Canadian Seed Security. Founded by Rabinowicz and funded by a generous donation from Gretchen Bauta of the Weston family, the program was launched in 2013 with a mandate to maintain regional varieties, adapt them to a changing climate and breed new diversity through participatory plant breeding in farmers’ fields.

"We want to give farmers the tools they need to grow great, healthy food that fits with their markets, production practices and climate,” Rabinowicz says, “So it’s about increasing the range of crops and varieties, yes, but it’s also about giving them access to seeds that have been bred for their production system as well. Right now that's just not the case for organic farmers."

Many of the seeds sold commercially in Canada, mainly for grain, undergo the Variety Registration Process, a federally regulated program that tests seeds in the field, growing them to ensure their viability before selling them to farmers. But the methods used are conventional, meaning most seeds are bred with the expectation that chemical inputs will be used. “They’re bred for [only] one model of agriculture,” Rabinowicz says. “We're not saying toss the system, but let's recognize that there are different modes of agriculture being practised in Canada, and there's a growing interest among farmers and consumers who are investing in more sustainable modes of farming. It’s time to evolve."

But what that evolution will look like is still unclear. "What do you do when you are working with hundreds of farmers on a breeding program?" she asks. "Our system isn't set up for that."

Still, Rabinowicz believes recognizing farmers for their leadership and expertise in plant-breeding is a good place to start. "You start looking at the loss of variety, the restrained access to diversity. The picture can start looking pretty bleak, but the thing I find so inspiring is that you can always create new diversity.”

Rabinowicz knows just where to find the market for that new diversity. Last fall, at her husband’s tearoom in Montreal, Rabinowicz helped USC Canada host its first-ever seed-totable dinner with its regional partners, pairing chefs with seed growers from Québec, who grew more than 40 “funky” varieties on a peri-urban farm. Varieties included the heritage Winter Keeper beet and Buffalo Creek squash and varieties of open-pollinated corn that were developed in the field. “Chefs get it,” says Rabinowicz, who believes it was the perfect way to see USC Canada’s philosophy come full circle. “We believe in conservation through use.”

But getting new diversity into a food system that is built for only a few crops will require convincing government and the public that biodiversity matters — that seeds matter.

"We want Canada to be a biodiversity champion and say that it is a big part of our climate-change strategy, of our food policy, of the future of agriculture in Canada as a driver of the economy — it touches on everything” Rabinowicz says. “It's our job to tell the story so Canadians understand the links and so Canadians care."

Back at USC Canada at 56 Sparks St., Rabinowicz looks out the windows in her corner office towards Parliament Hill. “That’s the PMO,” she says, adding slyly, “We like to think we’re keeping an eye on him.”

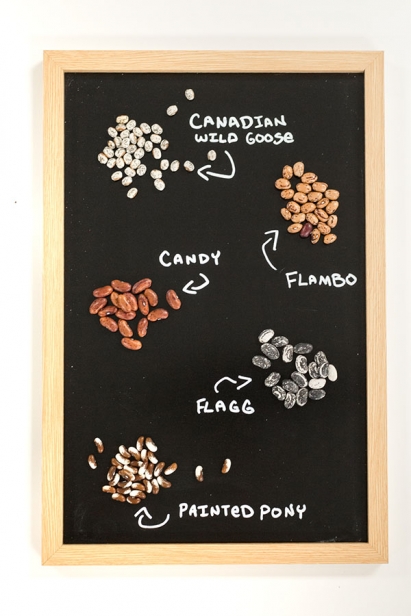

Strewn about the office are small packets of seeds, beans with names such as Dragon Tongue, Royal Burgundy and Blue Jay, a bean that was saved from near-extinction by seed savers.Rabinowicz hands them out. “Seeds teach me about abundance,” she says, “and they teach me about generosity.” Each packet contains a small handful of beautifully dried beans with the instructions “Plant. Grow. Save.” Six seeds that, in the right hands, have the potential to become hundreds, maybe thousands.

“When you save seeds, you end up with more seeds than you can handle,” she muses, “so what do you do with all that abundance? You give it to the people around you — you conserve diversity through using diversity, through sharing diversity, through eating diversity.”

USC Canada

600-56 Sparks St., Ottawa, Ont.

usc-canada.org, 613.234.6827