Canadian Chinese Food Culture

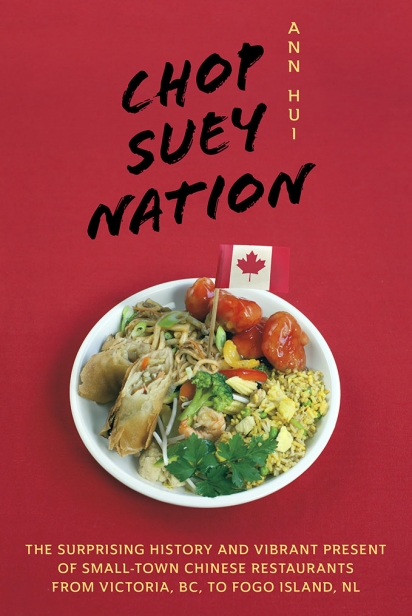

As I set off on a couple of road trips this summer, I passed through a pair of small Ontario towns with lone Chinese restaurants. I’ve driven these roads many times before, but until I read Chop Suey Nation, a book by Globe and Mail food reporter Ann Hui, I’d never given them a second thought.

In 2016, Hui put foot to pedal to drive across Canada to stop at as many of these restaurants as she could, on a journey that took 18 days and took her from Victoria to Fogo Island. What she discovered was food that was surprisingly Canadian and people who worked exceptionally long hours. She also found a huge part of her recent family history; her parents, too, had owned and operated a small-town Chinese restaurant in Abbotsford, B.C.

Chop Suey Nation interweaves the story of Hui’s father, his hard early life in China and his immigration to Canada in 1974, his subsequent decision to strike out on his own with a small restaurant in B.C., and that of hundreds of similar immigrants who arrived in Canada. What Hui found was that “over 150 years after the Cariboo gold rush, the Gold Mountain system was still intact.” What she means by the Gold Mountain system is the search for a better future. This is the story of Chinese migrants, typically from rural backgrounds, who left home to make a better living, returning home to build schools and houses, or sending money back to impoverished relatives.

There are hundreds of small restaurants from coast-to-coast-to- coast in Canada, many of them with the same look and feel. “The same vinyl booths. Menus printed in the same font, with the same categories and the same dishes. The same Wing’s brand plum sauce,” writes Hui. “In addition to understanding how these restaurants spread, I was still curious as to why so many of them seemed to look and feel exactly the same.”

Over the decades, word of mouth spread the news through Chinese communities that there was a reasonable independent living to be made in small-town restaurants. Hui dug up numerous advertisements for Chinese restaurants for sale and found that “often the ads emphasized a lifestyle for the entire family — good schools nearby, safe communities or grocery stores. What they were advertising were not restaurants, but new lives.” And with those new lives, they created a new kind of Chinese food, that of chop suey cuisine, a form of Chinese food that Hui herself had dismissed as “fake Chinese,” but that she ultimately discovered “was quintessentially Chinese. It was pure entrepreneurialism... They had created a cuisine that was a testament to creativity, perseverance and resourcefulness. This chop suey cuisine wasn’t fake Chinese — but instead, the most Chinese of all.”

Restaurant owners across the country adapted their recipes for the towns where they find themselves. In Deer Lake, N.L., this means chow mein, a dish typically made with noodles, is made with thin strips of cabbage, stir-fried with veggies and meat because, when the first Chinese restaurants opened, global trade hadn’t reached the far corners of Canada. It was impossible to get many basic ingredients, including the egg noodles typically used in this dish. In Calgary, Alta., ginger beef was born of customers’ desire for tender beef, combined with hints of sweet, salty, tangy and crunchy. In Quebec, Hui found a regional specialty that brought together fried macaroni, stir-fried pasta with soy sauce, meat and veggies. In Newfoundland, ribs that had been a hit in Vancouver didn’t work. The restaurant owner had figured out that “his new customers in Newfoundland were much, much older than the ones he’d had in B.C. The crunchy ribs were hard on their teeth. Or at least, on the teeth they had left,” Hui explains. “So he started braising his ribs, simmering them under low heat until they were soft and tender, falling off the bone. They were an immediate hit.”

Hui also found these small-town, small restaurants united by their sense of family. These are businesses — often handed down from one generation to the next, from aunts and uncles to nephews and cousins — that have sustained new immigrants and offered a freedom unknown on the Chinese mainland. And while some of these restaurant owners have settled into their communities, such as William Choy, restaurant owner and the mayor of Stony Plain, Alta., others tell stories of sacrifice and deep loneliness.

There’s Mrs. Xie in Drumheller, Alta., who told Hui that there were only seven or eight people in town with whom she could talk comfortably. “Of course, when we first came here it felt very lonely,” she said. “Now we feel better,” she said unconvincingly. In Thunder Bay, Ont., Hui met Norina Kartschi, a 50-year-old wondering whether she’d made the right decision in taking over the restaurant from her father. “I have huge regrets. My son is going to be 19, and I’ve barely spent time with him,” she said. And on Fogo Island, there’s Feng Zhu Huang, running a tiny restaurant entirely alone, while her husband runs a similar operation in Twillingate, N.L., in order to offer their three children a chance at a better life.

As Hui notes near the end of her book, “Their stories of what brought them here and why, I realized, were all the same. And all along, the question I’d been looking to answer had been wrong. It wasn’t what they came for, but who.”

Shortly after my eyes had been opened to small town Chinese restaurants, I noticed a new sign in my village of Wakefield, Que., offering Wen’s Chinese food, in large red and yellow letters. Wen Duoyao, a 27-year-old entrepreneur from Hull, bought the convenience store in the middle of Wakefield and opened his small restaurant at the back of the store in early summer. He cooks there on the weekends.

“I want to gain some experience in the restaurant business,” he explains. “I like cooking and I have always wanted to open a restaurant. But the real reason is that I really like working out and that has led me to develop an interest in healthy eating. One day, I’m going to open a gym and grill, so that you can exercise and then have a huge but healthy meal. For now, I’m learning about the business with my store in Wakefield.”

While this book is the story of Chinese-Canadian food, it is also Hui’s own family history, built on the back of chop suey cuisine. “I’ve been obsessed with the culture and history of this food since early in my life,” she says.

Her father, the central character, did not live to see the book’s publication, “which brings up complicated feelings,” she acknowledges. “But I’m so grateful to have been able to share his story with so many people.”