The End of Restaurants as We Know Them

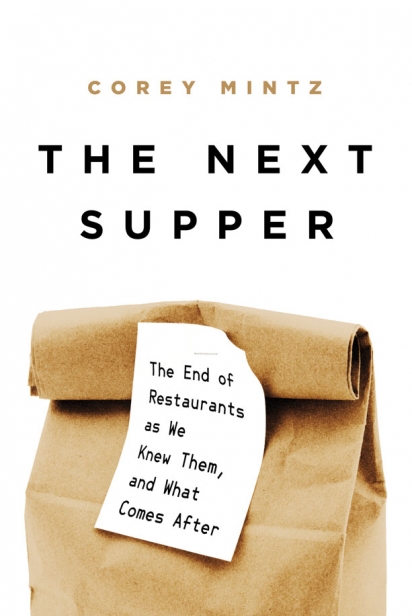

As more lockdowns deal a knockout blow to indoor dining in Canada, Corey Mintz’s new book, The Next Supper: The End of Restaurants as We Knew Them, and What Comes After, is a timely, if depressing way to spend several hours. But for anyone who loves to dine out or is interested in restaurants, it’s a must-read.

Mintz, a freelance food writer for the New York Times, Globe and Mail and Eater, among others, is also a former line cook, critic and the author of How to Host a Dinner Party. He knows the industry from the bottom to the top, including all the dirty secrets that, until recently, have been kept well-hidden from public view.

But COVID has changed all that. The pandemic has so completely shaken the foundations of an industry already crumbling around the edges, that these secrets have been forced out into the open. While previously we’d heard rumours of illegal wage practices and theft, dismal pay, brutally long hours, abusive chefs, constant inequities with distribution of tips, sex, drug and alcohol abuse, these claims were easy enough to ignore, given that only a few made it into the public discourse. Now Mintz’s book reveals how widespread these practices have become in order for restaurants to stay in business. The margins of the industry are so razor-thin that a catastrophe such as COVID has revealed the gory truth, guts and all.

Monday, March 16, 2020 was the day the restaurants died. Mintz’s book is a deep dive into what comes next. After all, you can only treat an illness if you know what it is, warts and all. Mintz offers us an unflinching view of the industry, from the tomato pickers in the fields of California, through fast food and chain restaurants, to the pinnacle of fine dining at restaurants such as Noma in Copenhagen and El Bulli in Spain.

However, even before this time, Mintz was trying to answer the question: “Knowing what I know about what goes on in restaurants, how food is produced, who grows it, who cooks it, who profits and who is exploited, how do I eat out and maintain my values?” The short answer isn’t clear. The long answer is 315 pages of this book.

Luckily for him, given the sometimes unpalatable prescription he is suggesting for the industry, Mintz hasn’t had much opportunity to eat out in restaurants since he researched and wrote this book, due to a toddler at home and a move to a new city mid-pandemic, “but I am happy to practise what I preach,” he says. “I want the dining choices I make to mean something. I want the money I spend to go to the kind of businesses I hope to see more of.”

The Next Supper offers eight chapters giving various perspectives on the food industry — from that of chef-driven dining, to the immigrant family-owned restaurant, or the franchisee-owned, publicly traded establishment, to fast food, ghost kitchens, technology and apps, take-out and delivery- food, the grocerant. He examines where the problems hide with each model and suggests possible solutions.

The chapter on the chef-driven restaurant is particularly pertinent in today’s COVID landscape because these are the restaurants most vulnerable to shutdowns. Fine dining doesn’t tend to travel well. And while the food may be passable out of a cardboard box, the ambiance, twinkling candles, luxurious wine cellar, personal service and general joie-de-vivre of the dining room experience doesn’t transfer. Many of these restaurants already operate on razor-thin margins, achievable only due to various poor labour and pay practices and the thorny issue of tipping.

“Though hidden from diners, the various mechanisms for cheating workers out of the money they deserve are not the problem. They are just the symptoms. The problem is a dining culture that has grown to expect extravagance without paying luxury prices,” Mintz writes.

For many chef-driven restaurants, the initial COVID shutdowns gave them the time to reconsider business practices and to think about how to do things differently. While there are no doubt several more, edible spoke with three Ottawa chefs who have thought long and hard about how to change the status quo in their restaurants.

Harriet Clunie at Das Lokal has made a huge effort to improve pay structures within her team. She has created a vastly complicated computer program to distribute tips appropriately between front and back of house. She has raised the basic wages of those working in the kitchen. She is also very aware of the mental health crisis that plagues restaurant workers.

Chef Justin Champagne-Lagarde, of the newly opened Perch on Preston Street, and Dominique Dufour, at Gray Jay on Echo Drive, have taken big strides towards offering a work-life balance to those with whom they work. Dufour ensures everyone on her team is paid equally. She has two teams, who work equal shifts over a four-day work week and tips are split evenly over the

whole week. “Back of house salaries are well above minimum,” she says. “Our aim is to provide a healthy living wage, raise living standards, reduce the amount of hours that employees work so that they are less overwhelmed and less stressed. There’s mistreatment in this industry that has gone unaddressed for too long. I want my colleagues to have access to their dreams, to have a home, afford a car and even raise a family while staying in the industry.”

Over at Perch, Champagne-Lagarde has pledged to pay above minimum wage, split tips evenly across the board and “be completely transparent with everyone who works with me. I want it to be a team,” he says, “with open dialogue, where everyone has a voice and people are not worried to speak out.”

Mintz praises several Toronto restaurants, including Richmond Station, MIMI Chinese, Restaurant 20 Victoria and Marben, all in Toronto, for their efforts to precipitate change. “Richmond Station eliminated tipping during the pandemic and has always had an eye to sustainability, practising whole animal cooking,” he explains, “while the owner of MIMI Chinese has always been interested in being a better employer. When we worked together on the line, he was often asking questions and talking about this subject.”

Mintz sees the seeds of change. “Recently, I talked with a restaurant owner who told me that at least once a service now, customers ask how tips are divided. Pre-pandemic, this just would never have happened. There are restaurant owners who are trying to make it as right as they can, numbers that would have been shocking just five years ago. They have to; all the rules have changed.”

While large parts of the restaurant industry are struggling to find a way out of debt, others are trying hard to create a virtuous restaurant, the subject of Mintz’s final chapter. Here, he explores restaurants conceived for social good. “Unfortunately, altruistic restaurants have a habit of going out of business,” he writes. But does it really need to be so?

Perhaps now is the moment we’ve been waiting for. A time when diners acknowledge the part they play in supporting a sustainable industry, when servers, cooks and chefs will no longer tolerate deplorable working conditions and poor pay, and when we vote with our wallets.

“We have an obligation to make a better normal. Following the forest fire of COVID-19, we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to regrow our food culture from its roots,” Mintz says.