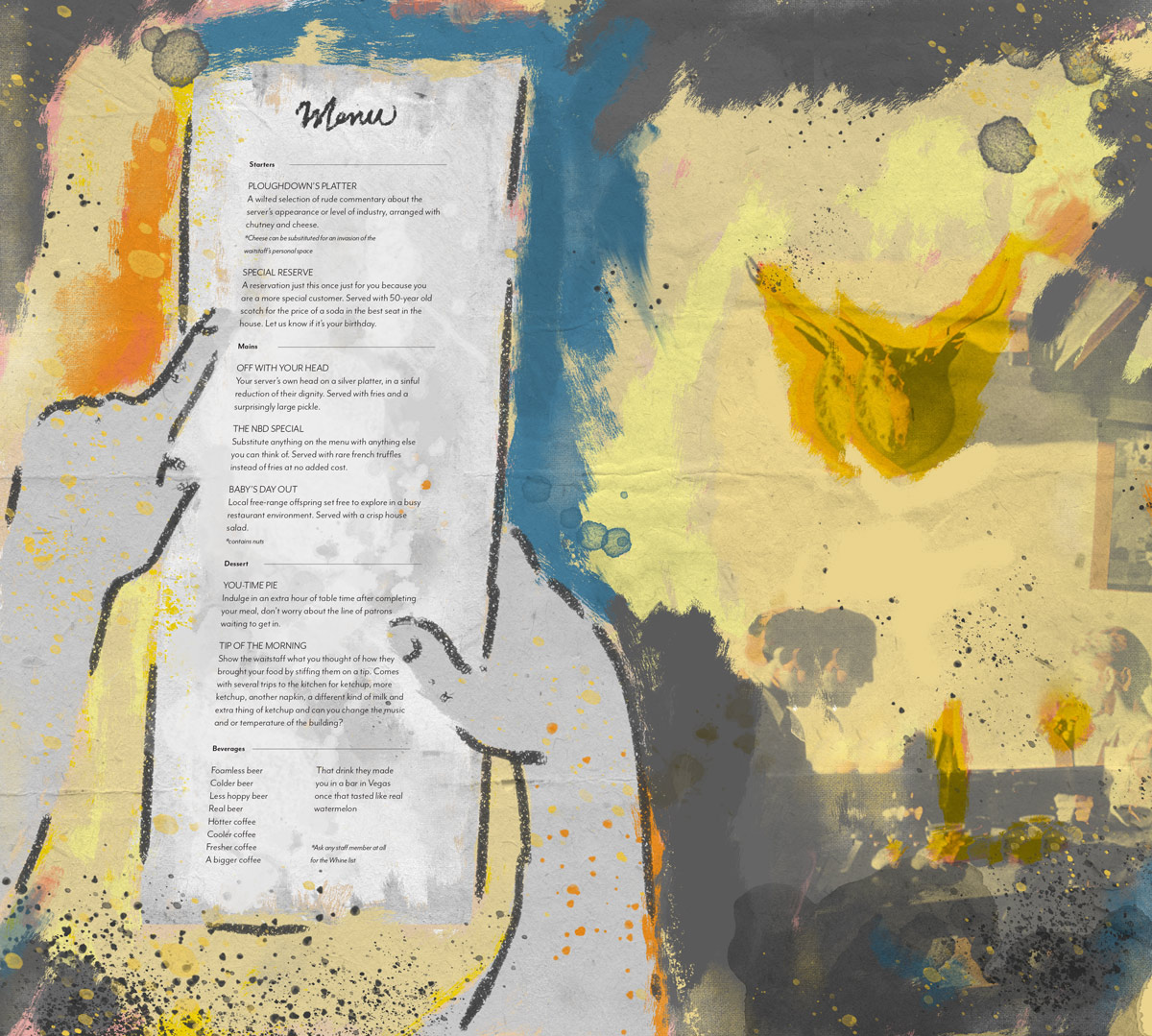

House Rules

One of the worst instances of a reservation gone wrong happened when a man and a woman, probably in their late-30s, walked into Town one busy evening with their two young children in tow. They had a reservation they told the host, who went to search the book to find it. Instead, he found nothing — no mention of their name on that particular night and not on the previous evening nor the next, not the following week, nothing. We were all stumped and quite concerned.

This was explained to the young family, with great apology, as the restaurant was already bursting at the seams. When asked if they would be willing to sit at Citizen, Town’s new sister space right next door, to enjoy a similar menu, the answer came like a dagger — “We’re not moving. Get someone else to move.”

If you have ever been to Town, you know “spacious” isn’t the first word you would use to describe it. The thruway between the banquets and bar is impossibly narrow at times, but lends itself to the darkly dramatic charm of the wildly busy and bustling Elgin-street eatery. Servers, hosts and guests alike have to negotiate the narrow passage and tables often need to be moved intimately close to their neighbours, so they can escape to the powder room — and they do, because that’s how Town works.

But this couple wasn’t willing to play the game. They stood directly in the thruway on a busy Friday night and refused to budge until we “fixed it.” Assuming it was our mistake, they would have us alter the laws of physics to reflect the fact that they were, indeed, the centre of the universe.

And that is what those of us in hospitality are often expected to do — defy the natural order of things. No matter how well we contort ourselves into impossible positions to squeeze between tables or manoeuvre scalding hot plates in front of guests who refuse to give way, we increasingly face challenges that seem insurmountable with no choice but to conjure solutions using only our earthly powers.

“The hurdles we have to jump [over] in order to give that warm, genuine feeling of hospitality keep getting harder,” says Jennifer Wall, who owns Supply and Demand Foods & Raw Bar with her husband and chef, Steven Wall. Hailing from the East Coast, the heartland of hospitality, the Walls know how to make someone feel tucked in — but that doesn’t mean the kids always go to bed without incident. If it isn’t a guest complaining about the music being too much or the lights too low or the restaurant being too loud (often because it’s busy — generally a sign of a good restaurant), hospitality is often hijacked before the guest even sits down.

“The time and labour we pour into making, changing and negotiating reservations, has gotten out of hand,” Wall says, “just to have them show up with half or double the number of people anyway — or not at all.”

Not only are people not showing up for their reservation without so much as a phone call or neglecting our multiple attempts to reach them while their table sits in financial limbo as we turn eager diners away just in case — if they do show up, it could be at a different time than they originally booked. “If we offer someone 6 p.m. because we are full at 7 p.m., more often than not, they still end up coming closer to 7 p.m.” Unlike most other industries, hospitality decrees that we do not turn them away (or bill the no-shows for lost income), rather we scramble to find them a seat and get their drinks and food out in a rush, pushing the tempo while maintaining good service, in hopes the following reservation won’t have to wait for their seat.

But, time and time again, that is exactly what they do. Whether intentional or not, guests have a way of overstaying their allotted time, regardless of the multiple confirmations that ensure they are aware of the length of time they have the table. “I have actually overheard tables tell their companions they won’t have to leave when their time is up,” Wall says. “‘They always figure out something,’ they say. But people don’t see the glasses of sparkling we're sending, on the house, to the guests waiting behind them.”

Nor do they see the panic it inflicts on a service team, which finds itself shuffling the entire floor plan for the night’s reservations or running to the basement to haul up an extra table, all during the middle of the rush. “The problem is we do always find a way to accommodate,” she says, “but that doesn’t mean we aren’t silently freaking out.”

Of course, much of the spectacle of hospitality is unseen, but when one side of the table isn’t playing their part, the show winds up sandbagged. The guest receives a less than stellar performance and those of us devoted to creating a successful experience walk away disheartened. Small wonder that waitstaff become frazzled and worn, often losing their ability to read their audience or even their desire to try.

Still, we keep at it because hospitality, when it works, is a deeply satisfying experience, for both sides of the table. “There is nothing like the feeling like you have nailed it,” Wall says. “It’s why we do this. But increasingly, fewer people are holding up their end of the bargain.”

Wall suspects we’ll start seeing more places like the recently opened Jabberwocky Bar on Somerset Street. “I love their rules,” she says, “They’re a great example of how to manage guest expectations.” Along with “Please limit your cell phone use” and “Don’t be shitty” underlined twice, they have a no-reservation policy, which they go on to explain in detail in their list of house rules. “Add-ons will be allowed when they arrive,” it says, “not before. That would be a reservation.”

I can’t say I blame them — when I first opened Wilf & Ada’s, I decided to forgo all the dickering and do the same. It meant one hell of a workout for me during our busy brunch service — between taking down the names and numbers of well over 200 people on our busiest days, I would send out rapid fire texts to the next person in the line-up, letting them know they were on a firm 10-minute countdown to grab one of our 30 highly sought-after seats. Not everyone was happy, but it worked. It’s been my experience that hospitality is most successful when the professionals are left to write the rules.

But when the house rules are broken, no one wins and reservations are simply one of many clauses, albeit the most explicit one, that make up the pact of hospitality. As owners and managers, we’re often the ones who are forced to walk a tightrope. Keeping our guests happy is paramount, but what about protecting our staff, and our businesses, from belligerent behaviour?

It veers from the disgusting (I would happily take scrubbing toilets everyday over the remove-all-gum-from-under-the-seats duty) to the repugnant — such as the time I asked a woman to remove herself from the premises of my restaurant after she screamed across the dining room floor at one of my staff. Her complaint, when I stepped in to inquire, was that she wasn’t being served as fast as the other diners. “I understand, but,” I said, unable to hide my incredulity, “you can’t scream at my staff.” She left in a fury and I looked on with pity at her teenage daughter who trailed behind. Not for her, mind you, but for the waitstaff and all other service folk in her future, her mother being such an excellent role model and all.

Just like the tantrum-throwing toddler who hogs the lion share of the teacher’s attention, those who blatantly disregard the pact of hospitality wind up ruining it for everyone else — their waitstaff, their fellow diners, and the painstakingly beautiful spectacle of service that can only happen when everyone shows up ready to play their part and behave accordingly.

Sure, sometimes we are the ones who break the pact, but rarely is it intentional and when we do, we tend to own our oversight and do everything in our power to make it right. More often than not, though, it isn’t us.

As it turned out, the couple did indeed have a reservation — just not at Town. It was at Courtyard Restaurant, after they had phoned the wrong restaurant to make their dinner plans. They wound up relenting and eating at Citizen, but they refused to eat their words. The only apologies I heard that night came from our side of the table.