'One of my Favourite Things is Caribou Tongue'

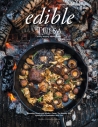

Trudy Metcalfe-Coe is at the front of the room at C’est Bon Ottawa’s cooking school and she’s sharing stories about her upbringing. She’s about to teach a class on Inuit Country Cuisine, featuring venison tartare and Arctic char served with potatoes and peas.

The tartare is fitting — not because she grew up eating tartare, but rather because she grew up eating a lot of raw flesh — often frozen and dipped in a bit of salt. Think of it as a savoury caribou or char popsicle.

Metcalfe-Coe is originally from Nain, Nunatsiavut, the Inuit land claims region in Northern Labrador and she is one of the very few Inuit chefs in the world. Self-taught, she started cooking at the age of 12 and, having lived in Ottawa for the past 30 years, she’s made it her mission to share her skills with those who want to learn about the culinary aspects of her culture. She teaches regularly at C’est Bon Ottawa, caters occasionally and participates in many culinary fundraisers around the city.

“I left Northern Labrador when I seven, but when we lived there, we would get apples and oranges in our stocking at Christmas time as a treat because it was so rare to get fresh fruit,” she says. “Eggs we got once a year in the spring when we’d go to the islands and collect them from the birds.”

She laughs and says “If I were teaching a traditional Inuit cooking class, we’d be done now because there wouldn’t be any cooking. Traditionally, we didn’t have any vegetables or fruit. It would be predominantly the protein.”

But that’s not what Ottawa audiences want, so she shares the traditional foods and presents them in forms more tempting to southern Canadian palates. “The proteins are from the Arctic, but there’s a lot of fusion.”

A signature dish

Asked to produce a dish that represents her culinarily, Metcalfe-Coe chose the two dishes from the cooking class. The tartare, because it’s served raw and that’s part of her heritage, and the char because it’s from the Arctic. She puts a spin on the char by blackening it, a technique she learned after eating red snapper fresh off a boat in Costa Rica.

“I ate it and thought ‘Oh, I’m going to make that when I get home’,” she recalls. Her spice blend, however, is different from the one she had in Costa Rica.

“My flavours are Newfoundland savory, smoked paprika, garlic powder, onion powder, granulated truffle salt and a little bit of cayenne, so there's just that little hint of heat,” she says, adding that she encourages students to adjust any of those seasonings to suit their tastes.

The potatoes she par-boils and then fries in a pan to crisp them up. And the peas she simply warms and tosses in butter. She associates them with fish because once her parents moved the family away from Nain, they had access to vegetables and always served frozen peas with fish.

For the tartare, she has often done it with caribou, but at the moment, there are caps on how much people can hunt and she wants any hunted caribou to stay in the community in which it’s hunted.

“There are only so many licences for the hunt,” she says. “I don't want to take out of a community what's needed there. When people go hunting, they hunt for their families, they hunt for the community and if I'm calling up asking for a couple of caribou, I’m taking it away from someone who needs it.”

She says bison is also a really nice meat for her tartare recipe, which also calls for red wine vinegar, Dijon, shallots, garlic, cilantro, lime zest, capers, truffle salt, garlic and two quail eggs — one for the minced meat, and one yolk with which to garnish the top of the dish.

The quail eggs speak to her family’s annual egg-hunting pilgrimage in the spring — an all too real Easter-egg hunt.

Fun cooking discoveries

Metcalfe-Coe says she sometimes will cook partially frozen fish because while she wants the skin to be crispy, she wants the inside to be moist and medium rare.

“Sometimes when I'm making my fish, I will cook it partially from frozen, because I don't want my fish to overcook,” she says. “This way, it’s going to be really nice and moist.”

When she visits her family in the north, she reduces ocean water to make salt.

“Five gallons of ocean water gives you two cups of salt,” she says. “When I’m travelling in the Arctic, I get water from wherever I'm at and I make the salt to bring back.”

Growing up

Metcalfe-Coe’s father was Inuk and came from Nain, and her mother was from Northern Newfoundland.

In Labrador, her father and grandfather hunted, giving them access to caribou, seal and ptarmigan.

“I remember really, really enjoying that food,” she says. “One of my favourite things that I’ve only had a couple of times in my life is caribou tongue.”

The first time she tried it, she was three years old and her mother was away because women had to leave town to give birth and she was pregnant with Metcalfe-Coe's brother. Her father was home with her, and he had some friends over and they were eating caribou tongues.

“My dad picked me up and gave me some, and to this day, it really brings back really strong memories of that night.”

The family moved to her mother’s native land when she was in Grade 2 and she remembers going down to the docks as a tween and collecting cod tongues from the fish harvesters.

“I still love cod fish to this day,” Metcalfe-Coe says. “If I’m going to go to Newfoundland in the summer, I will [try to] time it around the cod fishery so I can catch some cod to bring back. I couldn't go back this summer, but my brother and sister-inlaw were so generous. When I was flying back after working in the Torngat Mountains through St. John’s, they met me with a cooler full of cod fish that I now have as my winter supply.”

Metcalfe-Coe left Northern Newfoundland when she was 18 years old, as part of the Katimavik program, which provides travel and volunteer opportunities to young Canadians. Soon after that experience, she moved to Mont Tremblant, where she spent four years before moving to Ottawa at the age of 22.

Cooking as a passion

Metcalfe-Coe has always had a day job and cooking has been a side-hustle and passion project.

“When I first came to Ottawa, I was a single mom,” she says. “I used to do things like making cakes for hockey teams. One of my first catering jobs was to make 1,000 cookies. It helped pay the bills. The other thing I used to make is cheesecakes.”

She studied hotel management, Indigenous studies and museum technology at Algonquin College and then started working for community centres such as Tungasuvvingat Inuit, an urban services provider. She also worked for 14 years as general manager of Larga Baffin, a boarding home for residents of the Baffin region of Nunavut who come to Ottawa for medical services they can’t access at home. These days, she works at Inuuqatigiit Centre for Inuit Children, Youth and Families, currently as the post-secondary education elder.

Over the years, she’s taken leaves of absence from her day jobs to take on cooking jobs. Her summer 2023 gig as camp cook at the Torngat Mountains Base Camp, about 200 kilometres north of Nain, is one example.

“Anytime I get a chance to go and cook and I don’t have to keep it up full-time, I’m okay,” she says of that opportunity, which she hopes to replicate again this summer. “I loved it. Being home and close to family is great. It took me a long time to adjust to being back [in Ottawa.] I would be living there full time if I didn’t have a husband, children and grandchildren here.”

She also worked as the head chef at Mādahòkì Farm on a parttime basis for a year beginning in September 2022.

“I can’t be there all the time, and there was food going out with my name on it when I wasn’t there so I withdrew from that,” she says. “Also, [the centre] is very focused on First Nations and in my heart, I think it needs to have a First Nations chef.”

That said, she’s had some great experiences with the organization over the years, including regular participation in the Indigenous Experiences festival.

“The catering thing was never a career for me because I had my two kids and catering or cooking takes you away from family on all the special occasions,” she says. “I knew I didn’t want that.”

Inspirations and influences

Metcalfe-Coe always makes sure her plates are authentic.

“If I’m cooking duck, I want to make sure you know you’re eating duck,” she says. “I don’t want all kinds of sauces and flavours to mask it so you don’t know what you’re eating.” After that, she makes sure all the ingredients on the plate go together and that the courses of the meal flow nicely into each other.

“Everything on the plate is there with purpose,” she says.

Her mentors include Georges Laurier, owner of C’est Bon Ottawa.

“I’ve only known him for five or six years, but we’ve worked together at some pretty significant events,” she says. “We’re back and forth on things a lot. He’s my biggest supporter in so many ways.”

Mentors from afar include TV personalities Jamie Oliver and Jean-Pierre Bréhier.

Of Bréhier, she says: “He’s an excellent chef. I’ve never watched a show where I’ve questioned his technique. And he loves butter as much as I do.”

Meanwhile, she likes Oliver because he’s so inclusive. It’s a trait they clearly share.